Enter your email to receive alerts for this author.

Sign in or create an account to better manage your email preferences.

Are you sure you want to unsubscribe from email alerts for Alex Kirshner?

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In late July, I prepared to fly with my then fiancée from Los Angeles to Charlotte for our wedding. It was a special flight en route to the biggest day of our lives. It was also my birthday. Unfortunately, I had committed one of the gravest sins of modern American air travel: I had bought us basic economy tickets.

Neither my fiancée nor I gave much thought to what this meant. For one, we would likely not sit next to each other on the American Airlines flight. A bummer, but whatever—we didn’t want to pay the extra $100 each for the privilege. But then our flight kept getting delayed further and further. We tried to fly standby on an earlier departure, but another couple jumped us on the list at the last moment, and a gate agent said it was probably because we had booked into steerage. We wound up being delayed nine hours, but at least we got to sit together after most other passengers had bailed. I was mad about the delay, but I didn’t think until later to be mad about why I’d been passed over on the standby list, or why it took such a brutal delay for me to get to sit next to my partner.

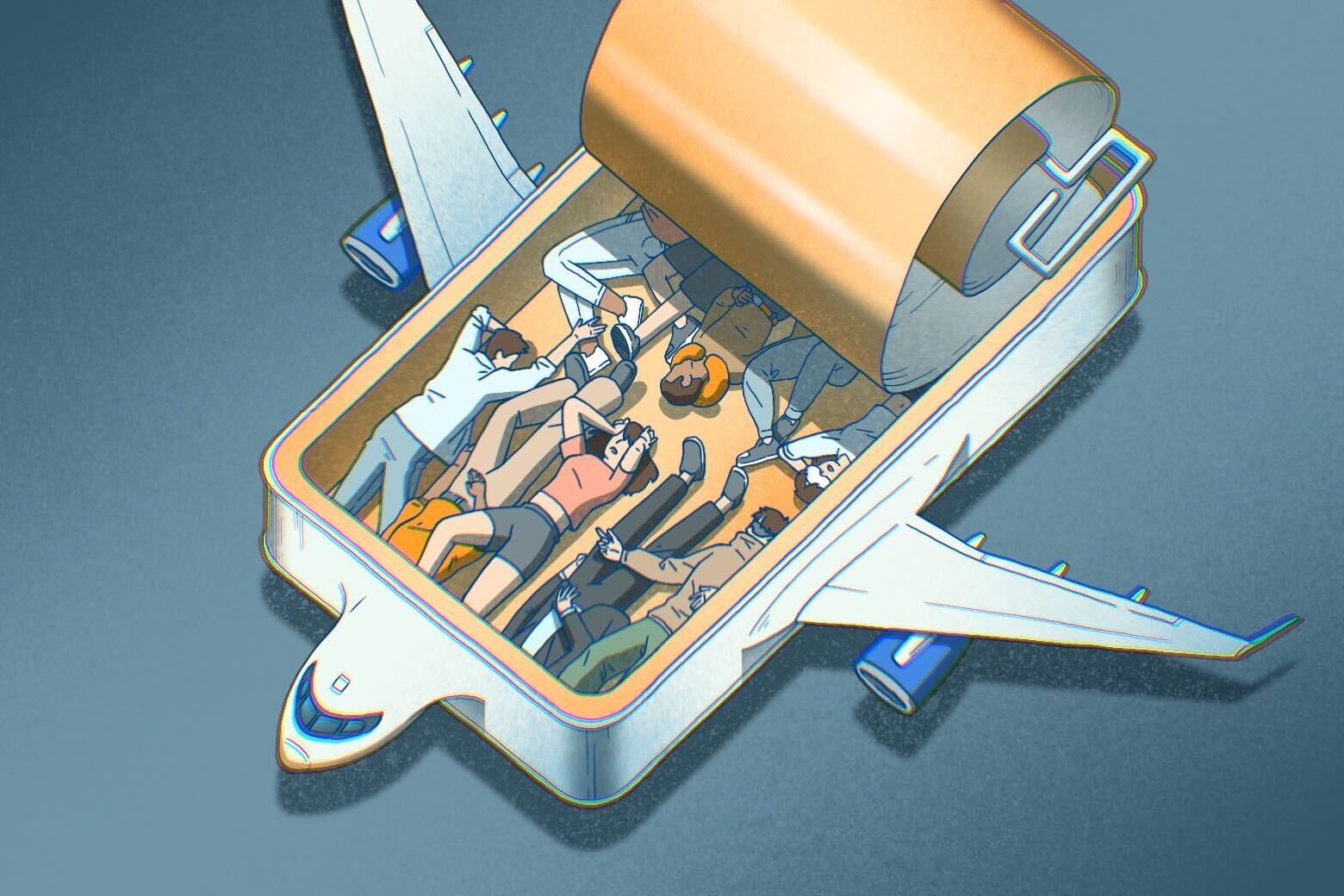

It used to be that the class delineator in airplane cabins was first class vs. everyone else. In the past decade, a new one has emerged: those booking regular economy tickets against people in this seedy new basic economy class. On United Airlines, basic economy flyers do not even get a carry-on, only a backpack or purse. On every major airline, passengers in basic economy board last and, most importantly, do not get to pick their seats. I had never thought much of it before—I opt for basic economy on almost every trip I book. As a 31-year-old who’s been paying for his own airfare for 12 years or so, I have never known a world where sitting next to your traveling companion is a typical, free part of a flight.

Not that I am complaining too much. The U.S. airline industry is well worth the price. These companies are great at accepting a few hundred of my dollars and dropping me off hours later at destinations that would otherwise require weeks and thousands of bucks to reach. I have a good experience on most of my flights, and so do you. The market research firm J.D. Power reports that just 10 percent of passengers had airline problems, mostly delays, last year. Overall passenger happiness has ticked up a little bit from 2024.

The problem is that we have played ourselves. By changing how we shop for flights, we have encouraged airlines to race one another to the bottom and to offer as few amenities as possible in the ticket classes that they market most widely. In fact, we’ve prompted these companies to make their offerings much worse, accepting each deterioration with a smile. The Google Flights–ification of flying has beaten back inflation in ticket pricing. It has also made flying less pleasant. Just as I haplessly accepted my fate days before the wedding, the flying public may have already missed its chance to break the cycle. Where you end up stuck on the plane is the most conspicuous sign of what we’ve all lost.

In 2002 Delta stopped paying commissions to old-school travel agents, kicking off a wave that its competitors rode. Cutting out a commission would make prices lower, ideally. The work of the agent who would pick up their phone and book your trip to the Big Apple shifted elsewhere. Some people did (and still do, I’m told) begin their flight-booking process on an airline’s website. But most do not. They go to online brokerages that take a fee, like Expedia, or to a simple search engine, like Google Flights. Not to impugn the integrity of anyone’s former travel agent, but that agent was probably less concerned than Google Flights with showing you the lowest possible price to get where you were heading.

That is the short story of how plane ticketing became a fishing expedition and basic economy the bait. Airlines realized that offering the lowest price for the lowest possible ticket class was key. “Over the years, they found out, just working with human nature, ‘I’ll offer a different fare where I’ll take things out and charge for them later, after people actually choose my brand,’ ” said Michael Taylor, a J.D. Power managing director who advises airline industry clients. “But they first have to choose my brand before I can start making any kind of money at all.”

This practice of disaggregation—stripping stuff out of the classic flying, in hopes of getting more out of passengers who want to retain those perks while bringing in the most price-conscious—has been good business for the airlines. If there was a chance to stop them all from moving in this direction, it was probably around 2008. That year, American introduced the first standard checked-bag fee, $15, along with a 50-pound upcharge threshold that remains the norm. Few of us stopped checking bags after that, or even when the cost soared to $35 or $40 per bag. Picking off seat selection, then, was easy money for the airlines.

“The financial incentive to do what they’re doing now is so great,” Taylor said. “The bag fee and the seat-selection fee and all those other disaggregated fees are really something that the airlines can showcase to investors, saying, ‘Look how much money we’re making.’ ”

How much? The airline industry makes a few billion dollars a year on seat-selection fees, according to a 2024 Senate report.

At first blush, this is a standard story of corporate greed. Easy pickings! But the question of what we should all want, as the flying public, is weirdly complicated. I know that this will sound strange if you have recently had an unpleasant flying experience, but we are living in an objectively great time to be nonrich people buying airline tickets. Non–business class tickets are only about $20 more expensive now than they were in 2000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (That link should return whenever the government reopens.) Inflationwise, we’re all making out like bandits.

Actually, not all of us. My wife and I don’t mind sitting apart on planes because we’re both thirtysomethings who want to do work or watch movies, but people who do care about sitting with their traveling party don’t get to enjoy the cursed miracle of basic economy. When I see a young father asking someone to switch seats to sit in a row with his wife and kid just before takeoff, my initial reaction is typically annoyance: Why didn’t this guy just buy the right ticket? Maybe I should be more gracious. The first Homo sapiens expected to sit with their family units on commercial flights, and bumping from basic economy to a fare with seat selection could easily cost a family $300. Eventually, I’ll try to game the system in the same way.

Of the three major domestic carriers, United has by far the worst basic economy tier. Unlike American and Delta, United won’t even let basic flyers bring a carry-on bag. But still, few seem to protest. If they did, it would probably show up in survey data, and it doesn’t: United economy and basic economy customers slot between Delta and American in satisfaction, just as they do in first class. As the years go by, fewer passengers will even remember a world in which picking your seat was standard fare. It’s probably just a matter of time until the other big players strip out carry-ons, as United has already done.

We should be more upset, though. It sounds dreamy to be paying only 22 additional dollars for something now than at the turn of the century, but it’s less dreamy when the product is worse. “The airlines say they’re saving you money by doing that because they’re keeping fares lower, but if you have to pay more to get the same thing you used to, it’s not really saving anything,” said Julian Kheel, the founder of Tripsight and operator of Points Path, a service that helps people maximize their airline miles. Those miles, by the way, are another delineator that can make the basic economy experience less pleasant for those without them.

At least some people do appear to be fed up. This summer, Google quietly began rolling out an option to exclude basic economy fares from the search engine on Google Flights. (How quiet? Enough that Kheel told me about it when we were talking, and that I had to open an incognito window and clear my cache to get the option.) Though tech giants are not immune from launching products that nobody was asking for, I suspect that basic economy has burned enough passengers that Google noticed. Have you also booked a “cheap” United flight only to realize that you’d be more than $100 in the hole if you wanted to bring a single piece of luggage with you to a wedding?

If the Googles and Expedias of the world made that exclusion the default search option, it might transform the way airlines structure their ticket offerings. But they won’t, because the public doesn’t want that. Almost all of us want the cheapest ticket—or at least the illusion of it, before we pay for add-ons.

“At the end of the day, most people book their airline tickets based on two primary factors,” Kheel said. “The first one, more than anything, is price, and that’s the price they first see at a search. And the second is convenience.” It speaks to our pickle as consumers that I have been stewing over this two-faced selling approach for weeks and am still not sure if I should want to stop it.

Absent aggressive pushback by consumers or intervention from the tech gods, the party that could do the most to reverse this tide is an airline. In theory, this is a ripe environment for a disrupter. The industry is awash in a fee-based model that is designed to hook and then milk customers. It should be easy enough for someone to make marketing headway by promising simpler pricing and an in-flight experience more like what existed in the old times.

But in fact, the airline industry is going the exact opposite direction. Even Southwest, the anti-fee zealot of the past 50 years, recently abandoned its two-bags-free policy and started charging just like everyone else. It will soon do away with first-come, first-served boarding and offer seat selection as a paid-for perk. The company also did away with same-day standby for a raft of lower tiers, something I learned when I strolled up to Phoenix’s airport six hours before a recent scheduled flight, confident I could hop on a better one. Nope.

An airline might be the single hardest business to create from scratch because of the enormous costs and regulatory hurdles associated with it. And no airline that already exists has any apparent interest in zigging while the market zags. As Taylor told me, “You get a lot of pressure from your own internal finance people saying, ‘Hey, we could be actually making more money if we did what everybody else is doing now.’ Would it create more loyalty and a happier flyer? Yes. Our data says yes, but they’re operating a business.” (Shoutout to the hedge fund guys now running Southwest.)

You could devise your own means of pushing back—by either not buying basic economy tickets or buying them, then blowing miles on upgrades to get back what you once would have gotten for your ticket price. That idea sucks, though. “Generally, you’re not going to get the most value for your points or miles by using them to upgrade from a paid ticket,” Kheel said.

There will be no mass consumer movement against companies that market the lowest possible ticket price, and there is no incentive for the airlines to market fares differently. Your only recourse, forever, is to act the same way you would fly on basic economy, like I almost did to my wedding day: alone.

Slate is published by The Slate Group, a Graham Holdings Company.

All contents © 2025 The Slate Group LLC. All rights reserved.

Slate relies on advertising to support our journalism. If you value our work, please disable your ad blocker. If you want to block ads but still support Slate, consider subscribing.

Already a member? Sign in here